By: Trish Fleming and Zach Jendro

Anyone who has scrutinized the claims of Judyth Vary Baker with an unbiased eye should be keenly aware that she has been less than consistent with many details of her story. Researcher David Reitzes has logged over 150 cited examples of how elements of her story have changed.[i] At the very least, this could mean that Baker’s keen photographic memory is not as reliable as she claims; at worst, it may mean that she has reworked and edited her account to suit her story, as needed. An examination of Baker’s evidence, as chronicled in her book Me and Lee, demonstrates no solid direct proof to back her claims of a romance with Lee Harvey Oswald. An historical account with such strong implications that is filled with so many discrepancies with no direct evidence to reinforce it requires a thorough analysis to attempt to set the record straight.

One element of the story of her summer in New Orleans which has been questioned is Judyth’s and Lee’s employment at a business called “Reverend James’ Novelty Shop.” In Baker’s account, “Reverend Jim’s” (as she claims it was locally known) was a multifaceted business that hired underemployed artists to paint souvenirs and trinkets, such as “ceramic alligators, maracas, and salt and pepper shakers,”[ii] for the local tourist market, as well as decorating Mardi Gras floats. Baker claims this work was available on a daily basis: employees were paid minimum wage in the form of cash for their labor, being a way to make “honest money.” Prospective employees were made to fill out paperwork attesting to their neediness, read a Bible passage, and sign a pledge to remain “sober and drug free.”[iii] According to Baker, “Reverend Jim’s” also had a storage facility that held “shiny alligators, ten feet tall, life-sized carousel horses, and colorfully-painted dragons, devils, and dinosaurs” which were created for “floats, carnivals, and shop windows.” [iv]The retail store front, which was located at 545 South Rampart Street, sold “rubber masks, wigs, African drums, Indian headdresses, costumes full of sequins, costume jewelry, and feathers… one section was stacked with Bibles, framed religious poems, and statues of the Good Shepherd.”[v] Baker states that, among other duties, she and Oswald painted “trolls, dwarves, and carousel horses.”[vi]

In the years since her story has been made public, internet researchers have questioned her account of this store. In fact, some researchers claimed she may have invented “Reverend Jim’s,” altogether.[vii] However, this business did, undoubtedly, exist. Information concerning the store is scarce, but the best available research indicates that a “Reverend William M. James’ Novelty Shop of Religious Articles” did, indeed, operate at 545 South Rampart. According to a business card housed in the “Voodoo” file at Howard-Tilton Library, Tulane University, the location was also home to a shrine to St. Jude. (Another shrine to St. Jude at the historic Our Lady of Guadelupe Church exists at 411 North Rampart in New Orleans. This location also houses a small Catholic gift shop, but according to Father Tony Rigoli, pastor of St. Jude’s, Reverend James was in no way affiliated with the church.[viii]) In an article by author and historian Carolyn Morrow Long, it is stated that Reverend James’ was in business from the early 1960s (c. 1962) until the mid-1980s,[ix] operating as a store that sold objects related to hoodoo (or folk magic practices). It is evident, then, that this business was at the location reported by Baker during the proper time period. But, how likely was it Judyth and Lee actually worked there?

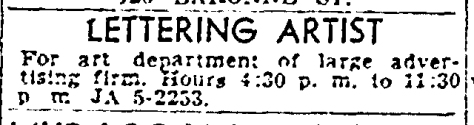

While the investigation into the assassination of President Kennedy (the Warren Commission) contained some glaring omissions, its research into the more mundane aspects of Oswald’s life was exhaustive. Numerous testimonies, affidavits and interviews were gathered in an attempt to piece together every known minute detail of his life. His time in New Orleans in 1963 was no exception. Among those interviewed were members of his mother’s family, the Murrets. His aunt, Lillian Murret, was questioned during her Warren Commission testimony concerning a brief period of time he stayed with the Murrets in the spring of that year. She refers to a job that Lee had interviewed for, doing some lettering work on Rampart Street. In her testimony, she claims that Lee had spotted this job in the newspaper and that he went down to this location, but he didn’t get the job. In her book, Baker asserts that this job on Rampart Street was doing lettering work for “Reverend Jim.”[x] (In addition, an article by John Delane Williams in The Dealey Plaza Echo, with comments by Judyth Vary Baker, makes this same claim.[xi]) An examination of the New Orleans Times Picayune for the dates in question (April 28- May 5) contains only one want ad for a lettering job (Figure 1). However, the ad is not for a religious shrine or souvenir vendor, it was for a “large advertising agency.” Research reveals that this advertising agency, The Ad Shop, was investigated by the FBI on November 29, 1963. It was, indeed, located on Rampart, 1201 South Rampart[xii].

The official account of Oswald’s employment history, tracked through his W-2 forms, personal finances, and pay information shows absolutely no trace of employment at Reverend James’. Oswald neglected to mention this job on subsequent visits to employment agencies. It is important to note that Baker claims that both she and Oswald were required to sign paperwork to work at “Rev. Jim’s” (probably including the necessary tax forms). How is it that investigations into Oswald’s time and his sources of income turned up absolutely no trace of this job, but jobs that he didn’t receive were traced and investigated? Did Reverend James pay people under the table at his shop? Would not authorities have asked who was doing the painting work and building parade floats in his shop? This would have undoubtedly added more pressure to a situation that, if we believe Baker, would have already have been dangerous for Reverend James.

South Rampart was known primarily as an African American neighborhood located in the Central Business District of New Orleans which has been closely linked to the birth of jazz. In the early 1900s, it was the home of famous musicians such as Louis Armstrong and Buddy Bolden and was the inspiration for the jazz standard “South Rampart Street Parade.” Asians, African Americans, and Jews called this area home for decades. A survey of the businesses of the 500 block of South Rampart around 1900 shows that the area was occupied by several second-hand stores operated by individuals with Eastern European surnames. The future site of “Reverend Jim’s”(545 South Rampart) was the home of N. Cohen’s “New and Second Hand Goods” store, which dealt in gold and “cast-off clothing.”[xiii] However, by 1963, this area had become run –down due to years of neglect. A former resident of the area, Gerri Delome, gave an 1985 interview about her memories of the neighborhood in the 1960s and stated, “As a child, the route of my many walks to Canal Street never included South Rampart Street. I was told the area was too rough for a little girl to venture alone… White people were a rarity on South Rampart. In fact, the area was considered so tough that many Blacks would not enter it after dark.”[xiv] Guns and knives were commonplace, and there were numerous unsolved murders and assaults. According to author Randy Fertel, by the mid-1950s, South Rampart was “one step up from Skid Row.”[xv] It was in this environment that naïve, 19-year-old Judyth claims she would walk to work at “Reverend Jim’s,” unescorted.

New Orleans of 1963 was deeply segregated along racial lines. Throughout Jim Crow-era Louisiana, schools, public transportation, residency, and employment were highly restricted until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the area around Rampart Street, the border between white and black was Canal Street. Everything north of Canal was generally white; everything south of Canal up to approximately the 600-700 block was black. This was not only true of property ownership, but social interaction and economic opportunity, as well. This line was clearly evident to Gerri Delome, for she recalled as a child, seeing the white owned Loew’s State Theatre with its “whites” entrance at 1108 Canal St. and its segregated “Blacks only” entrance on South Rampart.[xvi] “Reverend Jim’s” was no exception. In a 1996 interview, respected jazz historian and musician Tad Jones noted that Reverend William James was an “elderly black man.” [xvii] The idea of a black man hiring young white people to paint souvenirs for him in New Orleans in 1963 may have been illegal: a 1956 statute called for employers to create separate restroom and eating facilities for blacks and whites; if these facilities were not provided, the business owner faced heavy fines and jail time.[xviii] Building new restrooms and dining rooms would have been a very costly proposition for the owner of a small religious goods store. Not only would white people working for a black man have been unheard of, it could have been possibly dangerous. This was an era in which even the trailblazing Freedom Riders, who were protected by the glare of the national spotlight and the Justice Department, were being beaten with their lives being threatened, even being harassed by the New Orleans police at the airport.[xix] On South Rampart of the 1960s, a neighborhood in which a young waitress was killed for telling a man “to kiss her butt”[xx], violence against an elderly black man for breaking the rules of de facto segregation would not have raised an eyebrow among the white lawmen of New Orleans. Baker, a woman who discusses her moral opposition to segregation in her book (even stating that she and Oswald sat in the back of a bus to make a statement), made no mention of her supposed groundbreaking work for an African American man in segregated New Orleans.

It is beyond doubt, at this point, fifteen years after her “coming out” and more than five decades after the events themselves, that Baker’s account of what actually happened during her purported time with Lee OswaId has been, in the very least, altered. Some well-meaning people take her at her word, but without solid evidence, they are relying on faith. However, even faith cannot remove the serious doubts that have come to light regarding some aspects of her story. There are many examples of “holes” being found in her account, holes that Baker has attempted to shrug off. Her account of employment at Reverend James’ store is one of many. Her story is full of many unanswered questions. Why does Baker refer to Rev. James as “Rev. Jim?” His first name was William. It would seem unusual for a man to refer to himself as a shortened version of his own last name as though it were a first name. Why does Baker, someone who cares about civil rights, neglect to mention that the Reverend was African American? Why did she make no statement about the shrine to St. Jude or the shop’s hoodoo connections? Why did Baker make no references to the tough neighborhood in which the store was located, evidently feeling no nervousness walking alone in a very intimidating neighborhood, probably the lone white person in the area? In order to believe Baker’s story we would have to accept that Reverend James, a man who, according to Baker, made prospective employees read Bible verses before starting work, was breaking the law by paying employees at his manufacturing facility under the table, for no trace of either her or Oswald’s employment there can be found. (Baker states this was a place to make “honest” money, so it is reasonable to assume that Reverend James would have adhered to the laws.) We also must believe that Rev. James was willing to risk his own safety and livelihood by operating an integrated business in a hostile social environment and neighborhood, when running such an operation would have caused him much grief and negative attention. If he did own an integrated store, he would have had to provide expensive accommodations for both races, or he would have been breaking the law a second time. (Once again, Judyth never mentions this touchy topic.) We must also believe that there were, coincidentally, two lettering jobs known to Oswald (a fairly uncommon occupation, as only one advertisement for such a job was run in the newspaper, the source of the job information, according to Baker), with both jobs being on Rampart Street during the exact same week. Or, is it more likely that a woman who has been inconsistent numerous times over the years, has embellished her story, a story with no direct evidence to back it up? When one takes the lack of evidence into account, along with the contemporary and thorough investigation into the life of Lee Oswald, as well as the cold, hard realities of history, all that remains for a believer of Judyth to rely upon is faith. Then, perhaps it is fitting, that she has relied upon a man of faith to bolster her story. After all, she mentions Reverend James’ store eighteen times in her book. Evidently, Baker attempted to use the memory of a true believer to convert a whole new generation of believers to a new faith-based topic: the Judyth Vary Baker story.

[i] http://www.jfk-online.com/judyth-story.html

[ii] Judyth Vary Baker, Me and Lee (Trine Day 2010), 258.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Baker, Me and Lee, 257.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Baker, Me and Lee, 258.

[vii] https://groups.google.com/forum/m/#!topic/alt.assassination.jfk/o-8C3cDNY3E

[viii] Father Tony Rigoli, correspondence with authors, 20 Mar. 2015.

[ix] Carolyn Morrow Long, “The Cracker Jack: A Hoodoo Drugstore in the “’Cradle of Jazz,’” Louisiana Cultural Vistas Magazine, http://louisianaculturalvistas.org/crackerjack/ (accessed 20 Mar. 2015).

[x] Baker, Me and Lee, 272.

[xi] John Delane Williams and Kelly Thomas Cousins with Judyth Vary Baker, “Judyth and Lee in New Orleans,” Dealey Plaza Echo, no. 1 (2007), 24.

[xii] Warren Commission, Commission Exhibit 1911.

[xiii] “500 Block Rampart,” Archives of Tulane University, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University (New Orleans, La.)

[xiv] Gerri Delome, “I Remember South Rampart Street,” The Observer, Dec. 1985, 12.

[xv] Randy Fertel, “The Birth of Jazz and the Jews of South Rampart Street,” Tikkun, http://www.tikkun.org/nextgen/the-birth-of-jazz-and-the-jews-of-south-rampart-street (accessed 20 Mar. 2015).

[xvi] Delome, “I Remember South Rampart Street,” 12.

[xvii] Tad Jones, interview, 19 Jan. 1996.

[xviii] http://www.africanafrican.com/folder12/african%20african%20american3/anti-miscegenation%20laws/jimcrowlawslouisiana.pdf

[xix] Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice (Oxford University Press 2007), 175.

[xx] Bill Grady, “Barren Street Belies Glory Days,” New Orleans Times Picayune, Jun. 5 1990, B-2.

I like the article Trish but I’ve never gone to the trouble of reading “Me and Lee” (the old tagline Judyth throws at her doubters). I can’t recall Judyth ever bringing up Reverend Jim in the many interviews I’ve heard . Those friendly ones where she’s never challenged on anything and the interviewer gobbles it all up with a spoon.

LikeLike

It is pretty much a painful read. I do not like Judyth’s writing style. This has nothing to do with Oswald related stuff. Her writing is just bland. It has no zest to it. It is really straightforward (which can be a good thing) but her writing just plods and drags on… there is never a “payoff”. Never any “wow” moments… not entertaining.

-Zach

LikeLike

And the money just keeps rolling in for Team Judyth/Trine Day. I hear Wim owns a third of the company.

LikeLike